The Crowns of Florence <

Think of the soldering with which the orb of Santa Maria del Fiore was welded.

Leonardo da Vinci

Paris Ms. G, fol. 84v. Translation: Elizabeth Hughes

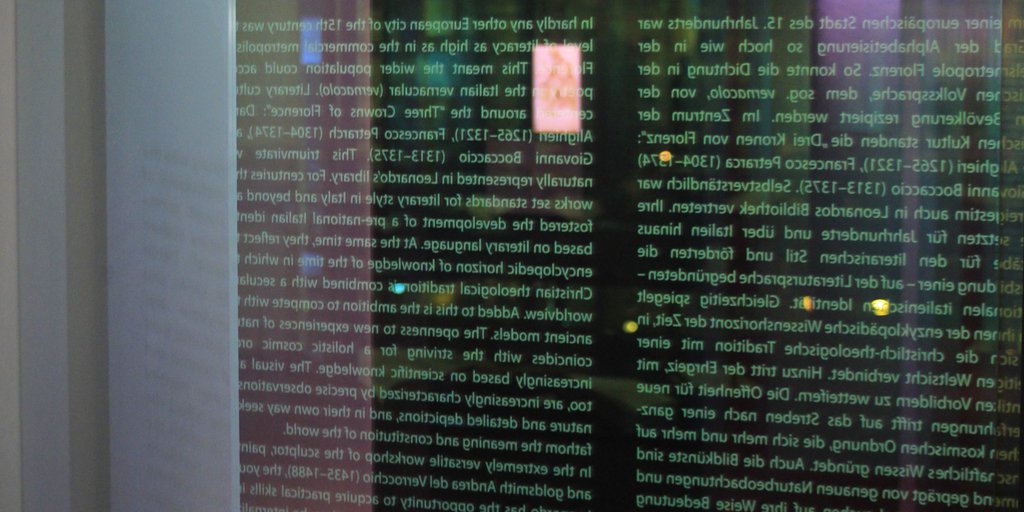

In hardly any other European city of the 15th century was the level of literacy as high as in the commercial metropolis of Florence. This meant the wider population could access literature in the Italian vernacular (vernacolo). Literary culture centered around the “Three Crowns of Florence”: Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374), and Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375). This triumvirate was naturally represented in Leonardo’s library. For centuries their works set standards for literary style in Italy and beyond and fostered the development of a pre-national Italian identity based on literary language. At the same time, they reflect the encyclopedic horizon of knowledge of the time in which the Christian theological tradition is combined with a secularist worldview. Added to this is the ambition to compete with the ancient models. The openness to new experiences of nature coincides with the striving for a holistic cosmic order increasingly based on scientific knowledge. The visual arts, too, are increasingly characterized by precise observations of nature and detailed depictions, and in their own way seek to fathom the meaning and constitution of the world.

In the extremely versatile workshop of the sculptor, painter, and goldsmith Andrea del Verrocchio (1435–1488), the young Leonardo has the opportunity to acquire practical skills in a wide variety of techniques. At the same time, he internalizes the aesthetic principles of artistic design. From his enthusiastic teacher, who was himself in possession of a respectable library, the ambitious young artist also learns further forms of knowledge, which flow into the conception of the works. These include engineering knowledge and construction principles, theological-philosophical foundations, and classical literary knowledge.

Mentors <

| 24.

Baptism of Christ ca. 1470–1475 |

The kneeling angel in profile on the left of this panel came from the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio (1435–1488) and has traditionally been ascribed to his pupil Leonardo. Not only early written sources but also the technical painting evidence confirm this. Whereas large sections of the panel are painted in the traditional tempera technique with the paint applied in dashes, the angel, Christ’s body, and the landscape are painted in oil, a technique that had only recently been adopted in Florence and which allowed completely new kinds of pictorial effects. Leonardo was probably permitted to finish—and update—the painting his teacher had begun some years earlier. In his biographical account of Leonardo (Life and Legacy E ●), Giorgio Vasari highlights the prodigious early talent of the young painter with an anecdote claiming that Verrocchio, overcome with frustration at his pupil’s achievement, never picked up a paintbrush again.

References

Bambach, Carmen C. 2019. Leonardo da Vinci Rediscovered. Vol. 1: The Making of an Artist 1452–1500. 4 vols. New Haven / London: Yale University Press, 130–134.

Caglioti, Francesco, and Andrea De Marchi, eds. 2019. Verrocchio, il maestro di Leonardo. Exhibition catalogue Palazzo Strozzi, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, 9.3.–14.7.2019. Venice: Marsilio.

Natali, Antonio, ed. 1998. Lo sguardo degli angeli. Verrocchio, Leonardo e il “Battesimo di Cristo.” Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale.

Windt, Franziska. 2003. Andrea del Verrocchio und Leonardo da Vinci. Zusammenarbeit in Skulptur und Malerei. Münster: Rhema.