Ancient Sources and New Experiences <

By nature, all good humans have a thirst for knowledge

Leonardo da Vinci

Codex Atlanticus, fol. 327v. Translation: Elizabeth Hughes

In the 15th century, scholars throughout Europe, especially in Italy, sought to raise knowledge of and familiarity with authors from ancient Greece and Rome to a new level. The goal of these humanists was to collect textual sources systematically from widely diverse fields of knowledge and make them accessible through commentaries, translations, and soon through printed editions as well. Encyclopedias such as those by the philologist and mathematician Giorgio Valla (ca. 1447–1499) made previously rare handwritten treatises generally available.

Florence was the first center of this movement, which was celebrated as the rebirth (Rinascita or Rinascimento in Italian, Renaissance in French) of ancient culture. The ideal of antiquity rapidly penetrated and inspired every cultural area, such as literature, architecture, and the visual arts. Parallel to this, the study of ancient traditions also promised resources for solving technical and scientific problems and tasks of contemporary life. Ancient natural scientists such as the Greek mathematicians Archimedes (ca. 287–212 BCE), Ptolemy (ca. 100–160 CE), and Euclid (ca. 300 BCE) were important authorities whose extant works formed a fixed canon. Their achievements also inspired Renaissance scholars in their own research and further observations.

Another canonical work is the Ten Books on Architecture by the Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius (ca. 70 BCE–ca. 15 CE). Its impact can hardly be overestimated and Leonardo da Vinci naturally owned an edition.

A contemporary counterpart are the writings of the philologist, master builder, and art theorist Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472). His architectural designs, like those for the façade of Santa Maria Novella in Florence, are considered incunabula of Renaissance architecture, while his writings on the genres of architecture, painting, and sculpture laid down the first theoretical basis for the new forms of design. The humanist Alberti was regarded by his contemporaries as a shining example of universal education. He was an inspiration for Leonardo, too, not least for the latter’s own theoretical writings on painting.

Leonardo's Berlin Library: Section 4 <

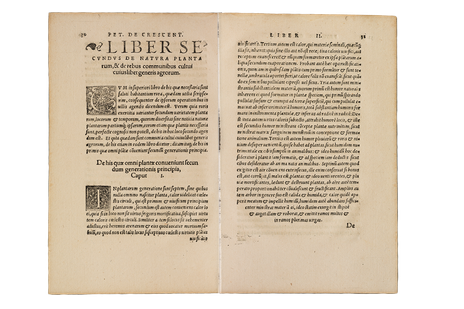

| 36.

De agricultura Basel: Henricus Petri, 1538 |

This book on agriculture by the Bolognese author Piero de Crescenzi (ca. 1233–1320) was one of the most popular manuals of its kind in the early modern period. Written in Latin at the beginning of the 14th century, the first printed edition, titled Ruralia commoda, appeared in 1471. An Italian edition is recorded in Leonardo’s book lists as “libro di piero cresscenzo.” Beginning with ancient works on agriculture like De re rustica by Lucius Columella (died ca. 70 CE), Crescenzi gave practical advice on every aspect of the agricultural system and rounded off with an annual survey of the work to be done in the fields. Leonardo used the text as a reference source for his botanical research (such as studies on tree growth) (55 ▲), and for his designs for irrigation systems or ideal facilities for grain storage.

References

Diekroeger, Mikey. 2019. In Leonardo’s Library. The World of a Renaissance Reader, edited by Paula Findlen. Stanford, CA: Stanford Libraries, 158,

no. 22.

Richter, Will, ed. 1995–2002. Petrus de Crescentiis (Pier de’ Crescenzi). Ruralia commoda. Das Wissen des vollkommenen Landwirts um 1300.

4 vols. Heidelberg: Winter.

Vollmann, Benedikt Konrad, ed. 2007–2008. Petrus de Crescentiis. Erfolgreiche Landwirtschaft. Ein mittelalterliches Lehrbuch. Vol. 3, 4. 2 vols. Bibliothek der Mittellateinischen Literatur. Stuttgart: Hiersemann.