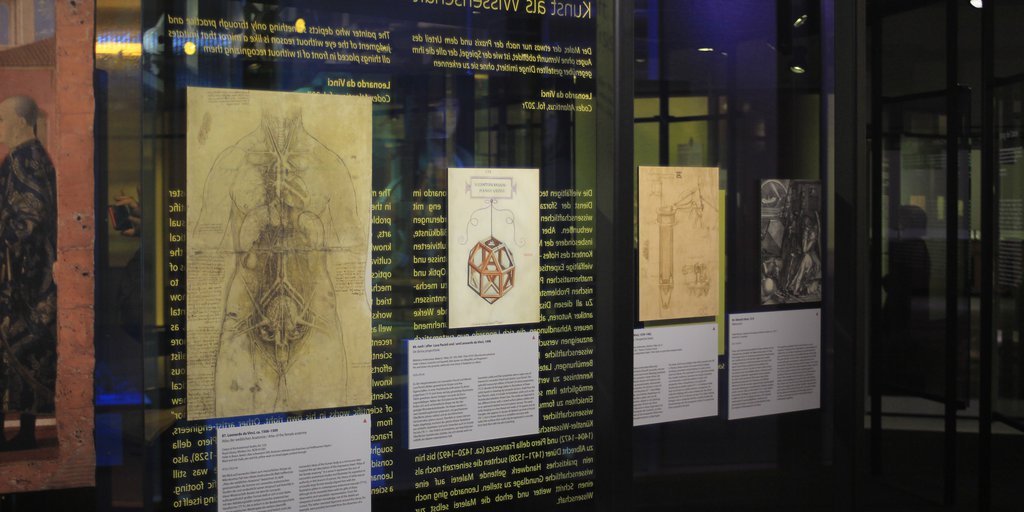

Science as Art, Art as Science <

The painter who depicts something only through practice and judgment of the eye without reason is like a mirror that imitates all things

placed in front of it without recognizing them

Leonardo da Vinci

Codex Atlanticus, fol. 207r. Translation: Elizabeth Hughes

The many and varied technical tasks Leonardo had to master in the service of the Sforzas were closely linked to scientific problems and challenges. But also the practice of the visual arts, especially painting, increasingly required theoretical knowledge and diverse expertise, particularly in the cultivated context of the court. This ranged from questions of optics and mathematical perspective construction to mechanical problems and medical knowledge. Leonardo now tried to learn systematically from the existing fundamental works by ancient authors related to all these disciplines, as well as from medieval sources and a growing number of more recent treatises. He expanded his library with specialist scientific literature and made concentrated and ambitious efforts to learn Latin and deepen his mathematical knowledge. This eventually enabled him to formulate new scientific insights of his own. He had now become an “author” of scientific works in his own right. Other artist-engineers, from Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) and Piero della Francesca (ca. 1420–1492) to Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), also sought to place painting, which at the time was still considered a purely practical craft, on a scientific footing. Leonardo went one step further and elevated painting itself to a science.

Perspectives <

| 82.

Camera obscura ca. 1508–1509 |

In Paris MS D, which is devoted to the human eye, Leonardo uses an experimental set-up to describe how the eye functions. This phenomenon had been known since antiquity and later, as the camera obscura, would form the basis of modern photography. The concentrated light rays of the illuminated object are forced through a tiny opening (spiraculo) into a completely darkened space (abitazione forte scura). There they can be registered on a sheet of white paper “so that you will see all the named objects … with their shapes and colors, but reduced in size and upside down [and as a mirror image; see the sketch], due to the aforesaid intersection of the rays … when the object is lit by the sun its images (simulacri) really seem to be painted on the paper.”

References

Fehrenbach, Frank. 2002. “Der oszillierende Blick. ‘Sfumato’ und die Optik des späten Leonardo.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 65 (4): 522–544.

Strong, Donald Sanderson. 1979. Leonardo on the Eye. An English Translation and Critical Commentary of MS D in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. New York / London: Garland.