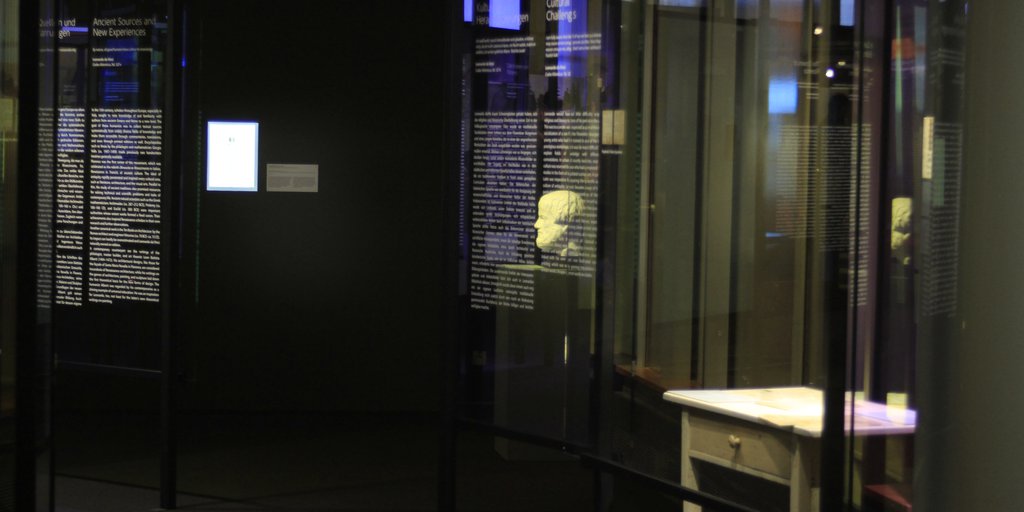

Cultural Challenges <

I am fully aware that the fact of my not being a lettered man may cause certain arrogant

persons to think that they may with reason censure me,

alleging that I am a man without letters. Foolish folk!

Leonardo da Vinci

Codex Atlanticus, fol. 327v. Translation: Mariangela Palazzi-Williams

Leonardo would have had little difficulty acquiring the religious and literary traditions of his period in the vernacular. This was to a certain extent expected as part of the intellectual socialization of a son from the Florentine bourgeoisie and a young artist who had been trained in one of the city’s most prestigious workshops. But it was far more difficult for him to explore fields of knowledge with different social connotations. In urban and courtly societies, access to high culture was reserved for those who had completed traditional studies in the form of a regulated curriculum. A command of Latin was imperative for acquiring the scientific and literary culture of antiquity. Leonardo became aware of his deficits, particularly in the cultivated surroundings of the Milanese court, and made great efforts to educate himself accordingly. He taught himself Latin and tried to master the current literary forms for conversation and written correspondence, all the while learning new technical and literary expressions to expand his vocabulary. Devising clever artistic subjects, such as those popular in the courtly milieu, also required a degree of familiarity with the subjects of classical education. Leonardo’s library reveals the growing diversity of fields of interest and work. This intellectual evolution, always closely linked with his own career, was facilitated not least by printing, which was rapidly gaining importance and made written works cheaper and more easily available.

Leonardo's Desk <

| 48.

ca. 1490 |

Leonardo had a penchant for fables and humorous literature. His library included not only numerous editions of Aesop (11 ■) but also satirical works and bawdy stories known as facetiae (facetious stories) (44 ■). He tried his own hand at writing in these two genres. His texts range from stylish well-crafted aphorisms to obscene droll stories—tailored to the tastes of different audiences. The sheet shown here contains moralizing fables about different types of trees amid scientific observations on plant growth. The trees in the fables include the citron, the peach, the nut tree, the fig, and the elm, each illustrated with little sketches and containing a moral message that the pursuit of as many and as large fruits as possible ultimately ruins the tree.

References

Leonardo da Vinci. 1952. Scritti letterari. Edited by Augusto Marinoni. Tutti gli scritti. Milan: Rizzoli, 46–47, 51.

Vecce, Carlo, and Giuditta Cirnigliaro. 2013. Leonardo. Favole e facezie. Disegni di Leonardo dal Codice Atlantico. Exhibition catalogue Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan, 11.6–8.9.2013. Novara: De Agostini.