Roots <

Writing so particularly about kites must be my destiny, because in my first childhood memory, it seemed to me that, as I lay in my cradle, a kite came to me and opened my mouth with its tail, and beat the inside of my lips with its tail several times

Leonardo da Vinci

Codex Atlanticus, fol. 186v. Translation: Elizabeth Hughes

Leonardo was the illegitimate son of the notary Ser Piero di Antonio da Vinci (1427–1504) and a farmer’s daughter, Caterina. He spent his childhood in the house of his paternal grandfather Antonio (d. 1464) in the rural area of Vinci, some distance away from the metropolis of Florence. This may have encouraged his personal initiative and ultimately his independent spirit.

Aside from basic religious knowledge and familiarity with the literary classics in the Italian vernacular, the cultural education of the broad merchant and notary class at that time mainly involved a practical mastery of the arithmetic techniques needed for commercial accounting. Families usually owned small libraries of around a dozen books that were passed down through the generations. The typical collection included an edition of the Bible—often in Italian—and other religious works (collections of acts of the saints, confessionals, psalms, and sermons) as well as the vernacular classics of the literary triumvirate of Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio. An arithmetic book (libro d’abaco) was indispensable for reference and as a textbook for everyday mathematical tasks. Additionally, the head of the family consecutively recorded memorable events and recollections (ricordanze) in a family album. Some family members also tried their hand at writing edifying texts. Leonardo’s half-brother Lorenzo (1480–1531), a wool merchant, wrote two short religious tracts. Most of the works were still handwritten codices. Book printing was still in its infancy when Leonard was young, but this would soon change rapidly, in Italy as elsewhere.

The Early Years <

| 18.

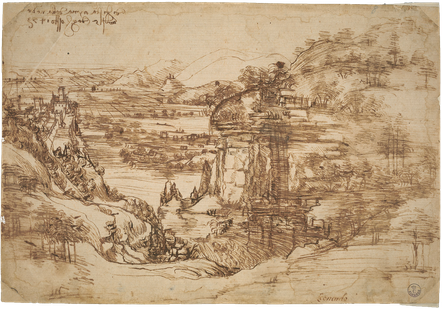

Landscape of the Arno Valley August 5, 1473 |

As if from a bird’s eye perspective, this wide view onto a river plain shows evidence both of natural erosion (a rock hollowed out by a waterfall) and human design (fortress architecture, grid patterns of drained swamps). The artistic novelty is that there are no active figures to be seen. It is disputed whether the young Leonardo portrayed a specific topography near his birthplace, or simply blended real recollections with imaginary visions.

What is certain, however, is the date the drawing was made. Leonardo, then aged 21, formally certified the picture at the top left in the style of a notary, with the words “on the day of Our Lady of the Snow, on August 5, 1473,” in the characteristic handwriting of the Florentine mercantile class, the mercantesca—and he was already using mirror writing.

Typical features of this fluid everyday script written without lifting the pen are a broad flow, simple elisions of the letters (ligatures), and numerous loops. Leonardo used this script all his life. Striking calligraphic similarities suggest that he probably learned it from his grandfather Antonio.

References

Bambach, Carmen C. 2019. Leonardo da Vinci Rediscovered. Vol. 1: The Making of an Artist 1452–1500. 4 vols. New Haven / London: Yale University Press, 136–140.

Chapman, Hugo. 2010. In Fra Angelico to Leonardo. Italian Renaissance Drawings. Exhibition catalogue, British Museum, London, 22.4.–25.7.2010, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, 1.2.–30.4.2011, edited by Hugo Chapman and Marzia Faietti. London: British Museum Press, 202 f., no. 49.

Nova, Alessandro. 2015. “‘Addj 5 daghossto 1473’. L’oggetto e le sue interpretazioni.” In Leonardo da Vinci on Nature. Knowledge and Representation, edited by Fabio Frosini and Alessandro Nova. Venice: Marsilio, 285–301, 398–412.