Challenges of Technology <

Mechanics is the paradise of mathematical sciences,

because through it one reaches the fruit of mathematics

Leonardo da Vinci

Paris MS E, fol. 8v. Translation: Elizabeth Hughes

Leonardo was able to develop his technical understanding and knowledge from an early age as an apprentice in the workshop of the gifted painter, sculptor, and goldsmith Andrea del Verrocchio, an expert in various artistic techniques and materials. Leonardo admired the machines that Filippo Brunelleschi had developed for the construction of the dome of the Florence Cathedral. (The copper sphere of the dome lantern that Leonardo later referred to in his writings was made in the Verrocchio workshop.) When Leonardo moved to Milan in 1482, where he had successfully applied for a permanent position at the Sforza court, primarily as a military engineer, he deepened his technical knowledge in many areas. An ambitious autodidact, he studied contemporary specialist technical literature and became a prototype of the artist-engineer. Two predecessors who particularly impressed him were Mariano di Jacopo Taccola (1382–1458) and Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1439–1501), both from Siena. The latter, like Leonardo, was a versatile artist-engineer in court service. Leonardo’s technical interests were fundamentally influenced by the extensive writings of Roberto Valturio (1405–1475), which belonged to his library. Leonardo’s wide-ranging interests, his love of experimentation, and his power of imagination, but not least his outstanding skills as a draftsman, soon enabled him to surpass his role models and opened up previously unknown possibilities in the visualization of technical relationships.

Leonardo's Berlin Library: Section 7 <

| 66.

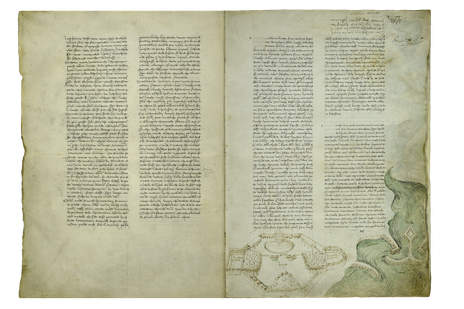

Trattato di architettura e macchine 1478–1481 |

The Trattato di architettura e macchine (Treatise on architecture and machines) is the most important theoretical work by the Sienese engineer, architect, sculptor, and painter Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1439–1501), whom Leonardo knew personally. This first version, an elegant parchment manuscript with text in two columns and drawings, was made around 1478–1481 in Urbino. To date, this is the only book that seems to have been identified as having been owned by Leonardo da Vinci. Twelve marginal notes (marginalia) apparently written by him reveal his careful study of the text in the years around 1504. At that time, Leonardo also used a second, later version of this work, from which he copied individual passages (Codex Madrid II, ca.1503–1504).

References

Bellosi, Luciano, ed. 1993. Francesco di Giorgio e il Rinascimento a Siena. 1450–1500. Exhibition catalogue Siena, 25.4.–31.7.1993. Milan: Electa.

Galluzzi, Paolo. 1991. Prima di Leonardo. Cultura delle macchine a Siena nel Rinascimento. Exhibition catalogue Magazzini del Sale, Siena, 9.6.–30.9.1991. Milan: Electa.

Tsagaris, Alexandria R. 2019. In Leonardo’s Library. The World of a Renaissance Reader, edited by Paula Findlen. Stanford, CA: Stanford Libraries, 170, no. 39.

Vecce, Carlo, ed. 2019. Leonardo and His Books. The Library of the Universal Genius. Exhibition catalogue Museo Galileo, Florence, 6.6.–22.9.2019. Florence: Giunti, 112, no. 10.1.