The Crowns of Florence <

Think of the soldering with which the orb of Santa Maria del Fiore was welded.

Leonardo da Vinci

Paris Ms. G, fol. 84v. Translation: Elizabeth Hughes

In hardly any other European city of the 15th century was the level of literacy as high as in the commercial metropolis of Florence. This meant the wider population could access literature in the Italian vernacular (vernacolo). Literary culture centered around the “Three Crowns of Florence”: Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374), and Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375). This triumvirate was naturally represented in Leonardo’s library. For centuries their works set standards for literary style in Italy and beyond and fostered the development of a pre-national Italian identity based on literary language. At the same time, they reflect the encyclopedic horizon of knowledge of the time in which the Christian theological tradition is combined with a secularist worldview. Added to this is the ambition to compete with the ancient models. The openness to new experiences of nature coincides with the striving for a holistic cosmic order increasingly based on scientific knowledge. The visual arts, too, are increasingly characterized by precise observations of nature and detailed depictions, and in their own way seek to fathom the meaning and constitution of the world.

In the extremely versatile workshop of the sculptor, painter, and goldsmith Andrea del Verrocchio (1435–1488), the young Leonardo has the opportunity to acquire practical skills in a wide variety of techniques. At the same time, he internalizes the aesthetic principles of artistic design. From his enthusiastic teacher, who was himself in possession of a respectable library, the ambitious young artist also learns further forms of knowledge, which flow into the conception of the works. These include engineering knowledge and construction principles, theological-philosophical foundations, and classical literary knowledge.

Leonardo's Berlin Library: Section 3 <

| 22.

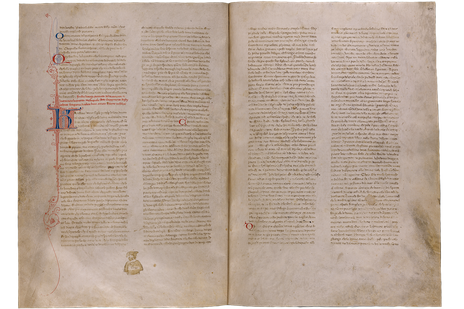

Decameron 1370 |

Boccaccio’s major work, the short story cycle The Decameron, is one of the most important and popular prose texts in European literary history. A group of young people from Florence takes refuge in the countryside during a plague epEademic and they amuse themselves during the 10 days there telling stories—quite often explicitly erotic tales—to each other. The manuscript in the Berlin State Library was written by Boccaccio himself and decorated with little figurative sketches in the margin. The page here shows the author making a rare comment in his own voice, defending his work against moralizing critics. He then departs from the overall narrative frame to tell a story himself. The protagonist, a sanctimonious hermit called Filippo, is pictured at the bottom of the page. To protect his naive son from sinful encounters, the hermit describes women to him like geese instead of humans. The son immediately wanted to keep a goose at home. Leonardo would probably have read The Decameron in his youth. His notes contain his own attempts at writing humorous novellas, ranging across the genre from didactic to coarse (48 ▲).

References

Bausi, Francesco, Maurizio Campanelli, Sebastiano Gentile, James Hankins, and Teresa De Robertis. 2013. Autografi dei letterati italiani.

Il Quattrocento. Vol. 1. Rome: Salerno Ed.

Cursi, Marco. 2007. Il Decameron. Scritture, scriventi, lettori. Storia

di un testo. Scritture e libri del Medioevo 5. Rome: Viella.

Idem. 2013a. La scrittura e i libri di Giovanni Boccaccio. Rome: Viella.

Idem. 2013b. In Boccaccio autore e copista, edited by Teresa De Robertis. Florence: Mandragora.