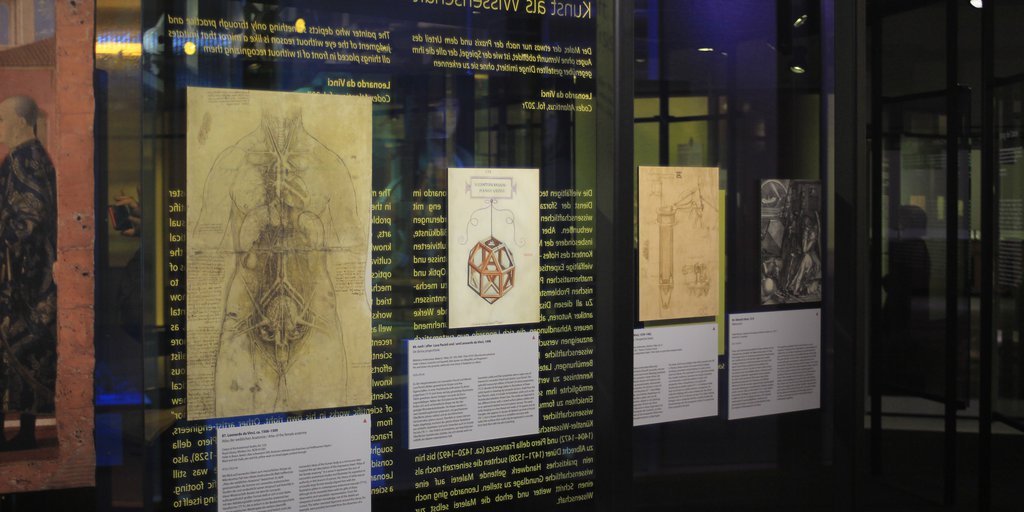

Science as Art, Art as Science <

The painter who depicts something only through practice and judgment of the eye without reason is like a mirror that imitates all things

placed in front of it without recognizing them

Leonardo da Vinci

Codex Atlanticus, fol. 207r. Translation: Elizabeth Hughes

The many and varied technical tasks Leonardo had to master in the service of the Sforzas were closely linked to scientific problems and challenges. But also the practice of the visual arts, especially painting, increasingly required theoretical knowledge and diverse expertise, particularly in the cultivated context of the court. This ranged from questions of optics and mathematical perspective construction to mechanical problems and medical knowledge. Leonardo now tried to learn systematically from the existing fundamental works by ancient authors related to all these disciplines, as well as from medieval sources and a growing number of more recent treatises. He expanded his library with specialist scientific literature and made concentrated and ambitious efforts to learn Latin and deepen his mathematical knowledge. This eventually enabled him to formulate new scientific insights of his own. He had now become an “author” of scientific works in his own right. Other artist-engineers, from Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) and Piero della Francesca (ca. 1420–1492) to Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), also sought to place painting, which at the time was still considered a purely practical craft, on a scientific footing. Leonardo went one step further and elevated painting itself to a science.

Leonardo's Berlin Library: Section 8 <

- 70.

Tetragonismus

Edited by Luca Gaurico. Venice: Giovanni Battista Sessa, 1503

- 71.

Miscellanea

13th c.

- 72.

Prospectiva communis

Edited by Facius Cardanus. Milan: Petrus de Corneno, 1482

- 73.

Opere

1468–1492

- 74.

Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni et proportionalita

Venice: Paganinus de Paganinis, 1494

- 75.

Divina proportione: Opera a tutti glingegni perspicaci e curiosi necessaria

Venice: Paganini de Paganinis, 1509

- 76.

Underweysung der Messung, mit dem Zirckel und Richtscheyt, in Linien, Ebenen unnd gantzen corporen

Nuremberg: Hieronymus Andreae, 1525

- 77.

Fasciculus medicinae. Similitudo complexionum & elementorum

Venice: Johannes and Gregorius de Gregoriis, 1500

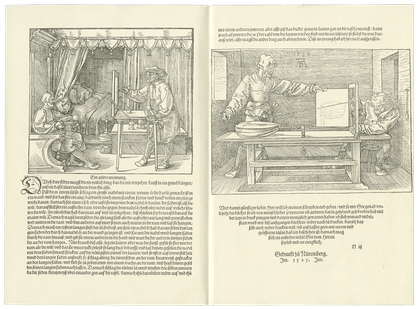

| 76.

Underweysung der Messung, mit dem Zirckel und Richtscheyt, in Linien, Ebenen unnd gantzen corporen Nuremberg: Hieronymus Andreae, 1525 |

The painter Albrecht Dürer from Nuremberg wrote this textbook on descriptive geometry as an introduction for young artists. His goal was to provide painting in his home country with the mathematical basis it already had in Italy. During his stay in Venice, he bought the latest Latin edition of Euclid’s Elements (Venice: Giovanni Taccuino, 1505) for the price of one ducat, as he noted on the title page. He also planned to get an introduction to the art of “secret perspectives” in Bologna, possibly, like Leonardo, from Luca Pacioli (and perhaps at the suggestion of the Venetian Jacopo de’ Barbari (78 ●), who worked in Nuremberg for a time). The woodcuts illustrate two detailed descriptions of the right methods of depicting foreshortening of perspective.

References

Großmann, G. Ulrich, ed. 2009. Buchmalerei der Dürerzeit – Dürer und die Mathematik. Neues aus der Dürerforschung. Vol. 2. Dürer-Forschungen. Nuremberg: Verlag des Germanischen Nationalmuseums.

Pollmer-Schmidt, Almut. 2013. In Dürer. Kunst – Künstler – Kontext. Exhibition catalogue Städel-Museum, Frankfurt a. M., 23.10.2013–2.2.2014, edited by Jochen Sander. Munich: Prestel, 190 f., no. 6.12.

Schoch, Rainer, Matthias Mende, and Anna Scherbaum. 2004. Albrecht Dürer. Das druckgraphische Werk. Vol. 3: Buchillustrationen. Munich: Prestel.