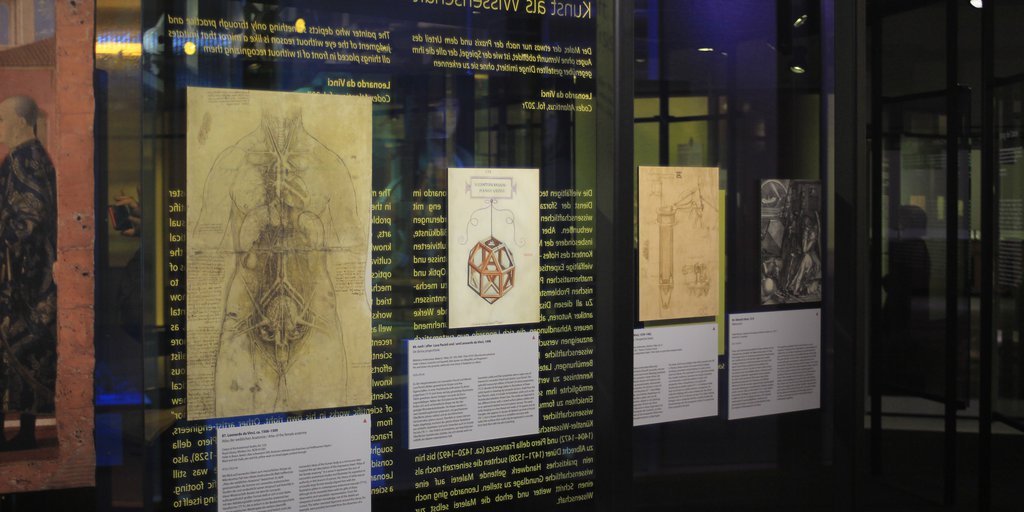

Science as Art, Art as Science <

The painter who depicts something only through practice and judgment of the eye without reason is like a mirror that imitates all things

placed in front of it without recognizing them

Leonardo da Vinci

Codex Atlanticus, fol. 207r. Translation: Elizabeth Hughes

The many and varied technical tasks Leonardo had to master in the service of the Sforzas were closely linked to scientific problems and challenges. But also the practice of the visual arts, especially painting, increasingly required theoretical knowledge and diverse expertise, particularly in the cultivated context of the court. This ranged from questions of optics and mathematical perspective construction to mechanical problems and medical knowledge. Leonardo now tried to learn systematically from the existing fundamental works by ancient authors related to all these disciplines, as well as from medieval sources and a growing number of more recent treatises. He expanded his library with specialist scientific literature and made concentrated and ambitious efforts to learn Latin and deepen his mathematical knowledge. This eventually enabled him to formulate new scientific insights of his own. He had now become an “author” of scientific works in his own right. Other artist-engineers, from Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) and Piero della Francesca (ca. 1420–1492) to Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), also sought to place painting, which at the time was still considered a purely practical craft, on a scientific footing. Leonardo went one step further and elevated painting itself to a science.

Geometric Art <

| 78.

Portrait of Fra’ Luca Pacioli and Disciple, ca. 1495–1500 |

08.02.02.03

With the cowl of his monk’s habit resembling a triangle, this double portrait by Jacopo de’ Barbari (ca. 1475–1516) shows the Franciscan friar and mathematician Fra’ Luca Pacioli as an authoritative geometry teacher. He was evidently associated with other illustrious pupils besides Leonardo—although the identity of the elegant young man in the lynx fur has never been definitively confirmed. The name inscribed in the frame of the slate is Euclid, whose Elements the master is using to demonstrate a theorem printed in the edition by Ratdolt (12 ■). Further to the right in the picture, in a costly red binding and identifiable from the spine, is Pacioli’s own recently published textbook, Summa de arithmetica (74 ■). The wooden dodecahedron and the transparent polyhedron—probably conceived as imaginary—refer to one of Pacioli’s areas of research, to which Leonardo’s art would shortly give shape (75 ■; 86 ▲).

References

Baader, Hannah. 2003. “Das fünfte Element oder Malerei als achte Kunst. Das Porträt des Mathematikers Fra Luca Pacioli.” In Der stumme Diskurs der Bilder. Reflexionsformen des Ästhetischen in der Kunst der Frühen Neuzeit, edited by Klaus Krüger, Rudolf Preimesberger, and Valeska von Rosen. Berlin / Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 177–203.

Baldasso, Renzo. 2010. “Portrait of Luca Pacioli and Disciple. A New, Mathematical Look.” The Art Bulletin 92 (1/2): 83–102.

Pollmer-Schmidt, Almut. 2013. In Dürer. Kunst – Künstler – Kontext. Exhibition catalogue Städel-Museum, Frankfurt a. M., 23.10.2013–2.2.2014, edited by Jochen Sander. Munich: Prestel, 190–191, no. 6.11.