The World, Great and Small <

The ancients called man a world in miniature, and that is well-said, because indeed man is made of earth, water, air, and fire, and thus his body is like the Earth. Just as man has bones as a support and framework for his flesh,

so the world has stone to support the Earth …

Leonardo da Vinci

Paris MS A, fol. 55v. Translation: Amanda DeMarco

Visual arts, science, and technology were closely intertwined in 15th-century Italy. At the same time, the individual disciplines were part of the evolution of a more comprehensive worldview and the intensive exploration of the relationship between the macrocosm and the microcosm.

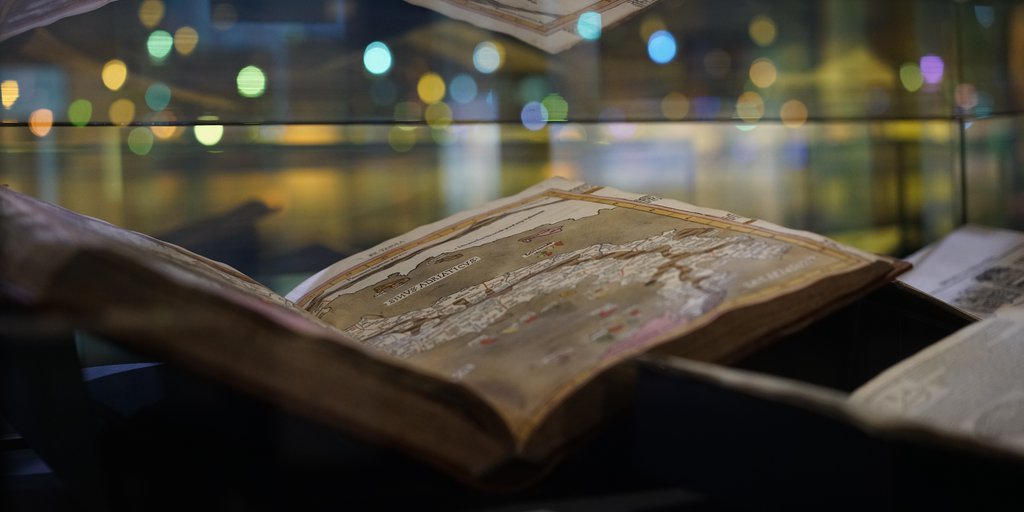

The worldview at large continued to rely on the geocentric tradition handed down from antiquity, with the Earth as the center of the universe surrounded by different hierarchically arranged spheres, from the sphere of water to the sphere of the fixed stars. The steady growth of knowledge, due not least to the geographical insights gained by voyages of discovery, increasingly called this view into question. In addition, intensified studies of nature in general and of the human body in particular, expanded knowledge of the world on the small scale.

It was hoped that this would lead not only to advances in science, medicine, and artistic representation, but also to a deeper understanding of the fundamental principles of life. The quest for such knowledge of nature was a central motif in Leonardo da Vinci’s creative work. The rapid development of printing continually increased the knowledge sources available to the artist-scientist, facilitating his search for an integrative worldview. At the same time, he was able to help shape this worldview through his own contributions: on a small scale through his analytical studies of the human body, and on a large scale through maps and depictions of astronomical phenomena.

Leonardo's Berlin Library: Section 9 <

- 89.

De situ orbis

Translated by Guarinus Veronensis and Gregorius de Tipherno Venice: Philippo Pincio, 1510

- 90.

Cosmographia

Edited by Nicolaus Germanus and translated by Jacobus Angelus.

- 91.

Alexandri Aphrodisiensis maximi peripatetici, In quatuor libros

meteorologicorum Aristotelis, commentatio lucidissima,

Alexandro Piccolomineo interpreteVenice: Scotus, 1548

- 92.

Sphaerae mundi compendium foeliciter inchoat

Venice: Octavianus Scotus, 1490

- 93.

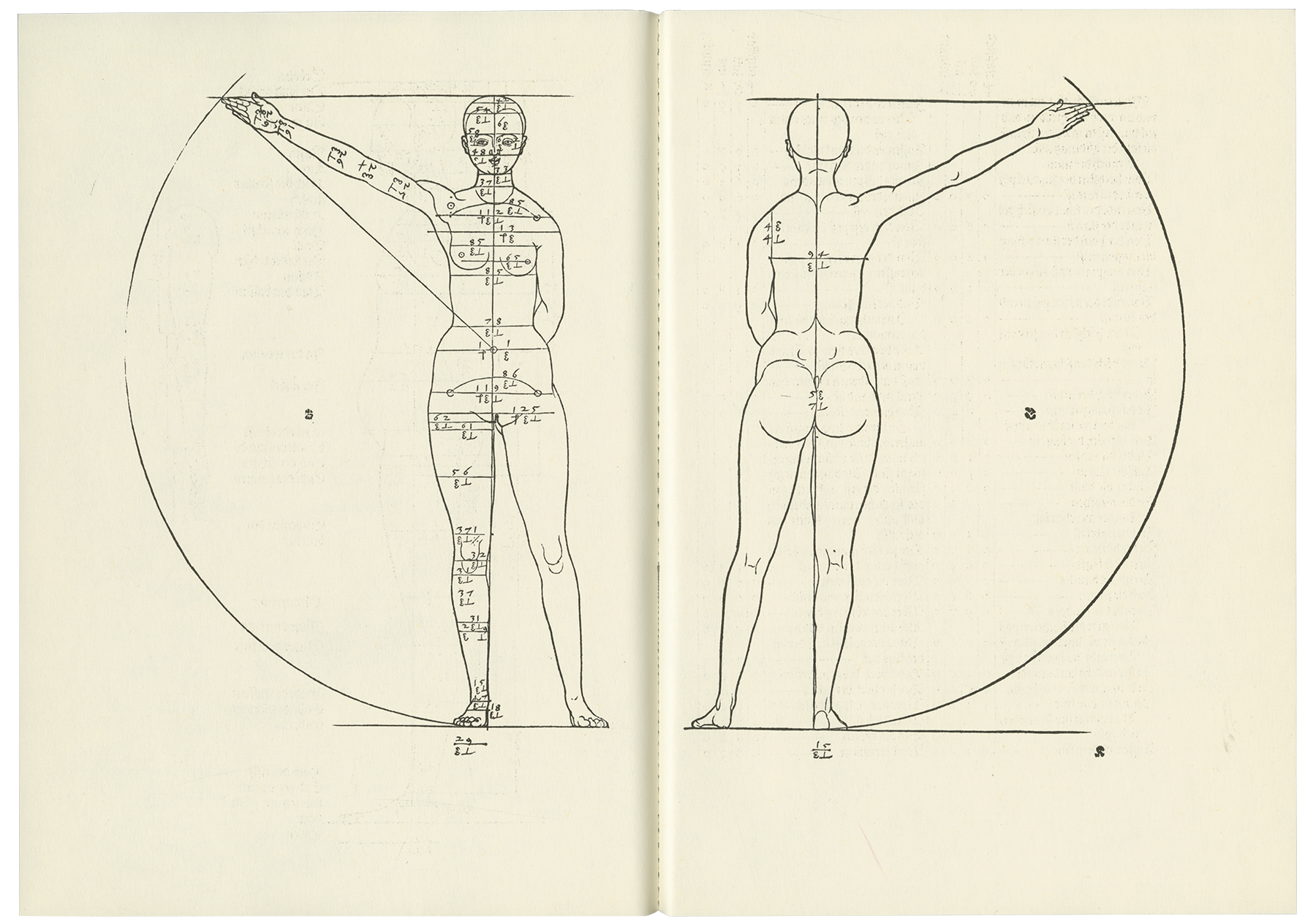

Vier Bücher von menschlicher Proportion

Nuremberg: Hieronymus Andreae, 1528

| 93.

Vier Bücher von menschlicher Proportion Nuremberg: Hieronymus Andreae, 1528 |

Like Leonardo, from 1500 onward Albrecht Dürer made an intensive study of anthropometry, the measurement and typical ideal proportions of the human body. Dürer’s starting point was the writings of Vitruvius (31 ■) and Pliny (52 ■). In his posthumously published proportion theory, he provided an introduction to the construction of different body types by assigning specific dimensional ratios to individual limbs. Dürer—unlike Vitruvius—developed proportional schemata not only for the male but also for the female body and the body of a child. In doing so, he decisively transcended the limits of the ancient authorities. An important didactic element on the visual level is that the book is illustrated throughout with exceptionally powerful and accurate woodcut diagrams. While Dürer tried to combine the visual arts with the “leading science” of mathematics, his texts were always aimed at practitioners, artists, and craftsmen to whom he wanted to make ancient and contemporary knowledge accessible in the vernacular.

References

Dürer, Albrecht. 2011. Vier Bücher von menschlicher Proportion (1528).

Mit einem Katalog der Holzschnitte, herausgegeben, kommentiert und in heutiges Deutsch übertragen von Berthold Hinz. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Großmann, G. Ulrich, ed. 2009. Buchmalerei der Dürerzeit – Dürer und die Mathematik. Neues aus der Dürerforschung. Vol. 2. Dürer-Forschungen. Nuremberg: Verlag des Germanischen Nationalmuseums.

Schoch, Rainer, Matthias Mende, and Anna Scherbaum. 2004. Albrecht Dürer. Das druckgraphische Werk. Vol. 3: Buchillustrationen. Munich: Prestel.