The Crowns of Florence <

Think of the soldering with which the orb of Santa Maria del Fiore was welded.

Leonardo da Vinci

Paris Ms. G, fol. 84v. Translation: Elizabeth Hughes

In hardly any other European city of the 15th century was the level of literacy as high as in the commercial metropolis of Florence. This meant the wider population could access literature in the Italian vernacular (vernacolo). Literary culture centered around the “Three Crowns of Florence”: Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374), and Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375). This triumvirate was naturally represented in Leonardo’s library. For centuries their works set standards for literary style in Italy and beyond and fostered the development of a pre-national Italian identity based on literary language. At the same time, they reflect the encyclopedic horizon of knowledge of the time in which the Christian theological tradition is combined with a secularist worldview. Added to this is the ambition to compete with the ancient models. The openness to new experiences of nature coincides with the striving for a holistic cosmic order increasingly based on scientific knowledge. The visual arts, too, are increasingly characterized by precise observations of nature and detailed depictions, and in their own way seek to fathom the meaning and constitution of the world.

In the extremely versatile workshop of the sculptor, painter, and goldsmith Andrea del Verrocchio (1435–1488), the young Leonardo has the opportunity to acquire practical skills in a wide variety of techniques. At the same time, he internalizes the aesthetic principles of artistic design. From his enthusiastic teacher, who was himself in possession of a respectable library, the ambitious young artist also learns further forms of knowledge, which flow into the conception of the works. These include engineering knowledge and construction principles, theological-philosophical foundations, and classical literary knowledge.

Brunelleschi's Dome <

| 29.

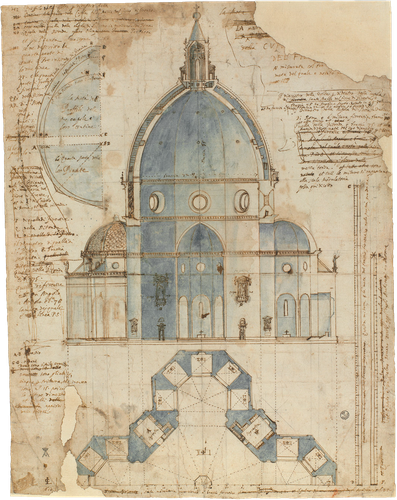

Plan and cross-section of the Dome of Florence Cathedral 1610 |

The Florentine painter and architect Lodovico Cigoli (1559–1613) spent his later years working mainly in Rome and for the pope. This drawing is a polemical attempt to demonstrate the superiority of the dome of Florence Cathedral compared to the domes of the most prominent Roman buildings of his time: the ancient Pantheon and the modern St. Peter’s Basilica. To prove this, he used the exact plan and cross-section of the crossing of Santa Maria del Fiore together with a comparison of the profile sections of all three domes drawn exactly to scale. He showed that Filippo Brunelleschi’s masterpiece of engineering technology, erected in 1420–1436 (30 ●)—visible testimony to the city of Florence’s primacy in the arts—was still an outstanding example even over a century later. It was not only the innovative rib construction with double-shell masonry that was epoch-making, but also the purpose-built machines developed by Brunelleschi, which also served Leonardo in part as a model for his machine designs.

References

Chappell, Miles L., and Lucia Monaci Moran. 2007. “Lodovico Cigoli, Matthäus Greuter and Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence.” Paragone Arte LVIII (75–76 (691–693)): 96–112.

Di Pasquale, Salvatore. 2002. Brunelleschi. La costruzione della cupola

di Santa Maria del Fiore. Venice: Marsilio.

Fanelli, Giovanni, and Michele Fanelli. 2004. Die Kuppel Brunelleschis. Geschichte und Zukunft eines großen Bauwerks. Florence: Mandragora.