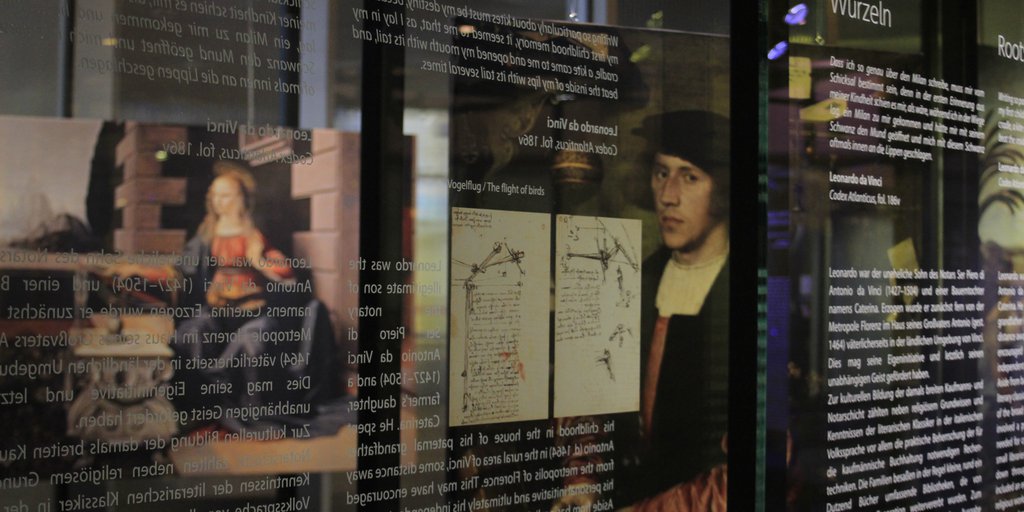

Roots <

Writing so particularly about kites must be my destiny, because in my first childhood memory, it seemed to me that, as I lay in my cradle, a kite came to me and opened my mouth with its tail, and beat the inside of my lips with its tail several times

Leonardo da Vinci

Codex Atlanticus, fol. 186v. Translation: Elizabeth Hughes

Leonardo was the illegitimate son of the notary Ser Piero di Antonio da Vinci (1427–1504) and a farmer’s daughter, Caterina. He spent his childhood in the house of his paternal grandfather Antonio (d. 1464) in the rural area of Vinci, some distance away from the metropolis of Florence. This may have encouraged his personal initiative and ultimately his independent spirit.

Aside from basic religious knowledge and familiarity with the literary classics in the Italian vernacular, the cultural education of the broad merchant and notary class at that time mainly involved a practical mastery of the arithmetic techniques needed for commercial accounting. Families usually owned small libraries of around a dozen books that were passed down through the generations. The typical collection included an edition of the Bible—often in Italian—and other religious works (collections of acts of the saints, confessionals, psalms, and sermons) as well as the vernacular classics of the literary triumvirate of Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio. An arithmetic book (libro d’abaco) was indispensable for reference and as a textbook for everyday mathematical tasks. Additionally, the head of the family consecutively recorded memorable events and recollections (ricordanze) in a family album. Some family members also tried their hand at writing edifying texts. Leonardo’s half-brother Lorenzo (1480–1531), a wool merchant, wrote two short religious tracts. Most of the works were still handwritten codices. Book printing was still in its infancy when Leonard was young, but this would soon change rapidly, in Italy as elsewhere.

Leonardo's Berlin Library: Section 2 <

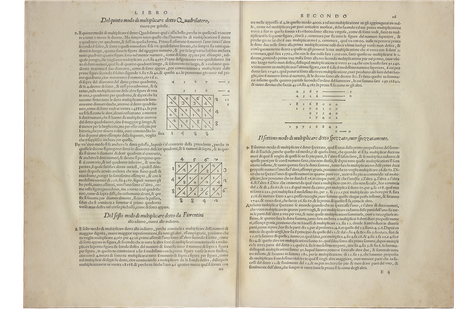

| 16.

Venice: Curtio Troiano, 1556 |

The General Treatise on Numbers and Measures by Niccolò Tartaglia (ca. 1499/1500–1557) is one of the most important mathematical encyclopedias of the early modern period. It contains treatises on practical problems in arithmetic, geometry, and algebra that often occurred in daily mercantile life. Like Leonardo, the compiler, an arithmetician born in Brescia, had acquired his knowledge as an autodidact. Tartaglia even stated that he had taught himself to read and write. The open spread shown here explains, among other things, a multiplication method, which was also practiced in Florence and probably learned by Leonardo as a boy (114 ▲), although the textbook was produced somewhat after his lifetime. The same method (“backwards” or “from behind”) is also described by Leonardo’s friend Luca Pacioli in his arithmetic book Summa de arithmetica (74 ■).

References

Giusti, Enrico, and Paolo D’Alessandro. 2020. Leonardi Bigolli Pisani vulgo Fibonacci. Liber abbaci. Biblioteca di Nuncius 79. Florence: Olschki.

Pizzamiglio, Pierluigi. 2012. Niccolò Tartaglia nella storia. Con antologia degli scritti. Milan: EDUCatt Università Cattolica.