Science as Art, Art as Science <

The painter who depicts something only through practice and judgment of the eye without reason is like a mirror that imitates all things

placed in front of it without recognizing them

Leonardo da Vinci

Codex Atlanticus, fol. 207r. Translation: Elizabeth Hughes

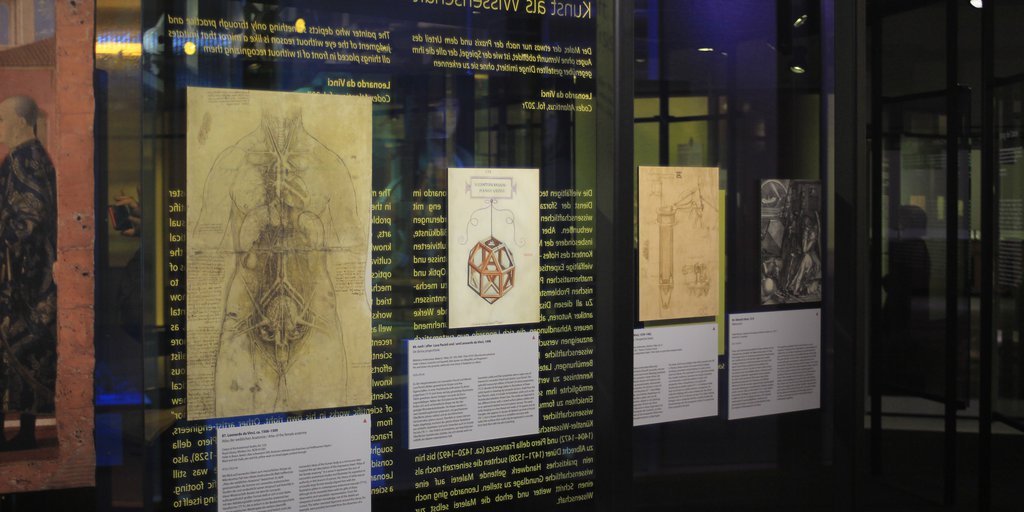

The many and varied technical tasks Leonardo had to master in the service of the Sforzas were closely linked to scientific problems and challenges. But also the practice of the visual arts, especially painting, increasingly required theoretical knowledge and diverse expertise, particularly in the cultivated context of the court. This ranged from questions of optics and mathematical perspective construction to mechanical problems and medical knowledge. Leonardo now tried to learn systematically from the existing fundamental works by ancient authors related to all these disciplines, as well as from medieval sources and a growing number of more recent treatises. He expanded his library with specialist scientific literature and made concentrated and ambitious efforts to learn Latin and deepen his mathematical knowledge. This eventually enabled him to formulate new scientific insights of his own. He had now become an “author” of scientific works in his own right. Other artist-engineers, from Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) and Piero della Francesca (ca. 1420–1492) to Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), also sought to place painting, which at the time was still considered a purely practical craft, on a scientific footing. Leonardo went one step further and elevated painting itself to a science.

Geometric Art <

| 80.

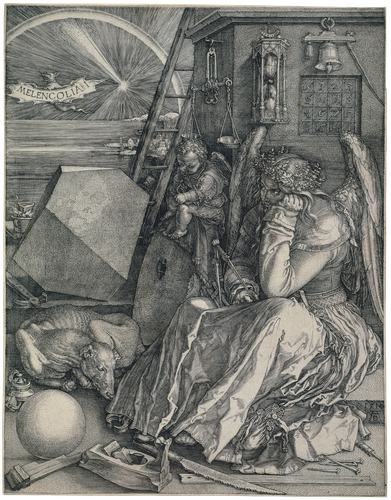

Melencolia I 1514 |

This engraving, probably Dürer’s most famous, is, as an enigmatic “thought picture,” dedicated to a representation of melancholy, the somber temperament associated with the god and the planet Saturn, and traditionally also with artists. The personification of this somber temperament broods idly and yet with great concentration, resting her head on her clenched fist. The book in her lap and the compass in her hand lie unused, along with all the other mysterious objects around her. The bat presents the title of the engraving against a backdrop of the nocturnal sky lit up by cosmic phenomena. Some of the scattered tools lie around in an odd state of neglect, almost pleading to be used for their craft, whereas the compass and ruler (76 ■) and other instruments like the scales and hourglass tell us of Dürer’s belief in measurement and numbers as the universal basis of art. Geometric bodies like the sphere and rhomboid, and the magic square of numbers on the wall, also point to the inherent laws of mathematical regularity.

References

Böhme, Hartmut. 1989. Albrecht Dürer. Melencolia I. Im Labyrinth der Deutung. Frankfurt a. M.: Fischer.

Klibansky, Raymond, Erwin Panofsky, and Fritz Saxl. 1990. Saturn und Melancholie. Studien zur Geschichte der Naturphilosophie und Medizin, der Religion und der Kunst. (1. edition 1964). Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp.

Schuster, Peter-Klaus. 1991. Melencolia I. Dürers Denkbild. 2 vols. Berlin: Gebr. Mann.