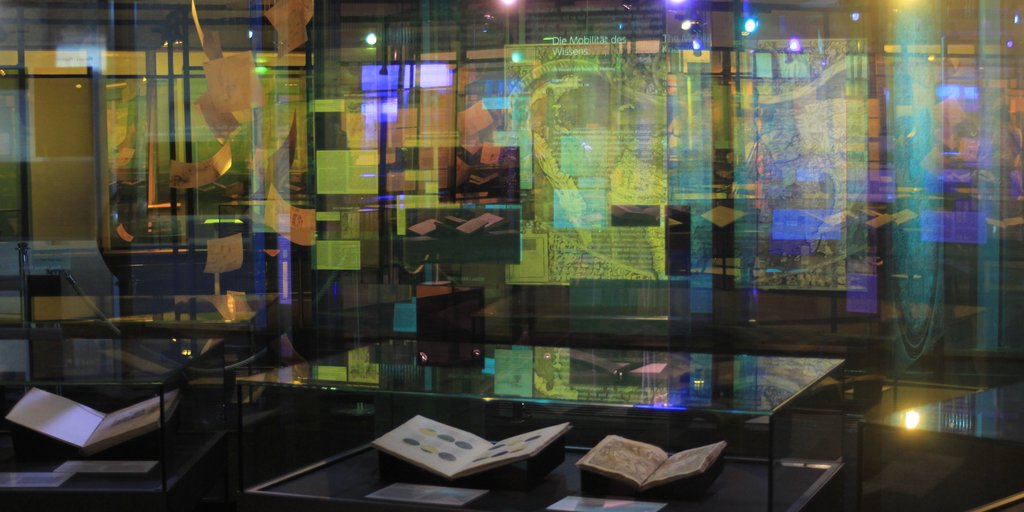

The Mobility of Knowledge <

Wisdom is the daughter of experience

Leonardo da Vinci

Codex Forster III, fol. 14r

The knowledge gathered by Leonardo in his personal library is collective knowledge. It is based, first, on a long tradition dating back to antiquity, and second, on increasing human mobility since the late Middle Ages. Oceanic navigation and the growth of printing created another major push. Merchants traveled along the major trade routes and maintained branches in important urban centers; participants in the Crusades brought knowledge to Europe, especially from the Arab world; international scholars and students exchanged ideas at the universities thanks to the universal language of Latin; artists and master builders traveled across Europe and beyond in search of lucrative commissions and the latest artistic developments. Explorers on voyages of discovery undertook daring expeditions to hitherto unknown continents and brought back new knowledge, while the colonizers who followed them seized the newly discovered territories—with terrible consequences for their inhabitants. This new knowledge was recorded and published in the form of reports, stories, in increasingly precise geographical maps, and in new scientific treatises. The result was a constant expansion and transformation of the worldview. In Leonardo’s library, too, the share of this new knowledge continued to grow over the years.

Leonardo's Berlin Library: Section 10 <

| 100.

Libro dela Cosmographia Antwerp: Bontius, 1548 |

In 1524—a few years after Leonardo’s death—Petrus Apian (actually Peter Bienewitz, 1495–1552), who came from Leisnig in Saxony, published the first edition of his Cosmographicus Liber, which clearly followed the tradition of Ptolemaic geography. By the end of the 16th century, this important work for navigational theory, particularly the version edited by the Dutch author Gemma Frisius (actually Jemme Reinersz), had been reprinted in over 30 editions and numerous translations. The copy shown here was the first Spanish edition, printed in the international port of Antwerp. It includes a world map with the heart-shaped projection developed by Apian.

References

Röttel, Karl, ed. 1995. Peter Apian. Astronomie, Kosmographie und Mathematik am Beginn der Neuzeit. Exhibition catalogue Ingolstadt, 7.10.–12.11.1995. Buxheim-Eichstädt: Polygon-Verlag.