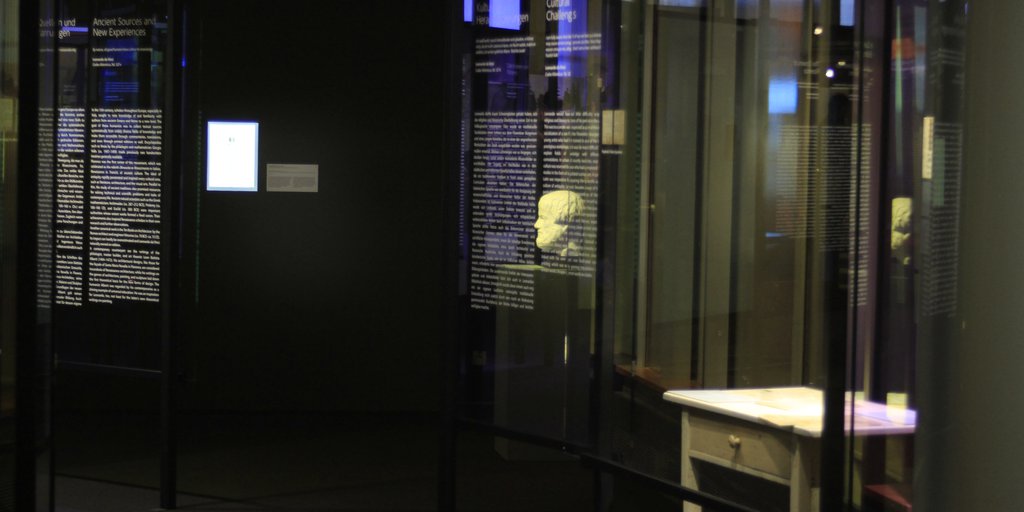

Cultural Challenges <

I am fully aware that the fact of my not being a lettered man may cause certain arrogant

persons to think that they may with reason censure me,

alleging that I am a man without letters. Foolish folk!

Leonardo da Vinci

Codex Atlanticus, fol. 327v. Translation: Mariangela Palazzi-Williams

Leonardo would have had little difficulty acquiring the religious and literary traditions of his period in the vernacular. This was to a certain extent expected as part of the intellectual socialization of a son from the Florentine bourgeoisie and a young artist who had been trained in one of the city’s most prestigious workshops. But it was far more difficult for him to explore fields of knowledge with different social connotations. In urban and courtly societies, access to high culture was reserved for those who had completed traditional studies in the form of a regulated curriculum. A command of Latin was imperative for acquiring the scientific and literary culture of antiquity. Leonardo became aware of his deficits, particularly in the cultivated surroundings of the Milanese court, and made great efforts to educate himself accordingly. He taught himself Latin and tried to master the current literary forms for conversation and written correspondence, all the while learning new technical and literary expressions to expand his vocabulary. Devising clever artistic subjects, such as those popular in the courtly milieu, also required a degree of familiarity with the subjects of classical education. Leonardo’s library reveals the growing diversity of fields of interest and work. This intellectual evolution, always closely linked with his own career, was facilitated not least by printing, which was rapidly gaining importance and made written works cheaper and more easily available.

Leonardo's Berlin Library: Section 5 <

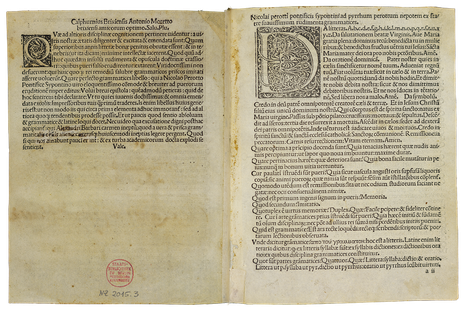

| 42.

Rudimenta grammatices Venice: Bonetus Locatellus, 1490 |

The Rudimenta Grammatices by the humanist Niccolò Perotti (ca. 1430–1480) was one of the 15th century’s most widely read grammars. Leonardo used it to teach himself Latin in Milan in the 1490s. Grammar exercises from the years 1494 and 1498 can be found in his MSS H, I (112 ▲), Codices Forster II and Arundel, and on numerous sheets in the Royal Library in Windsor.

References

Fanini, Barbara. 2019. “The Library of a ‘Man without Letters’.” In Leonardo and His Books. The Library of the Universal Genius. Exhibition catalogue Museo Galileo, Florence, 6.6.–22.9.2019, edited by Carlo Vecce. Florence: Giunti, 32–41.

Fenech, Nicholas. 2019. In Leonardo’s Library. The World of a Renaissance Reader, edited by Paula Findlen. Stanford, CA: Stanford Libraries, 149, no. 9.

Vecce, Carlo, ed. 2019. Leonardo and His Books. The Library of the Universal Genius. Florence: Giunti, 100, no. 6.11.