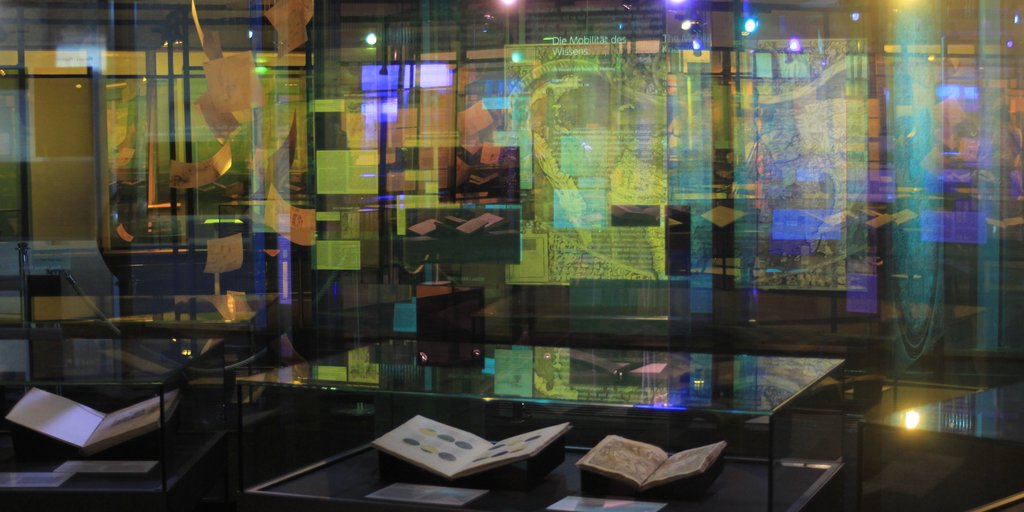

The Mobility of Knowledge <

Wisdom is the daughter of experience

Leonardo da Vinci

Codex Forster III, fol. 14r

The knowledge gathered by Leonardo in his personal library is collective knowledge. It is based, first, on a long tradition dating back to antiquity, and second, on increasing human mobility since the late Middle Ages. Oceanic navigation and the growth of printing created another major push. Merchants traveled along the major trade routes and maintained branches in important urban centers; participants in the Crusades brought knowledge to Europe, especially from the Arab world; international scholars and students exchanged ideas at the universities thanks to the universal language of Latin; artists and master builders traveled across Europe and beyond in search of lucrative commissions and the latest artistic developments. Explorers on voyages of discovery undertook daring expeditions to hitherto unknown continents and brought back new knowledge, while the colonizers who followed them seized the newly discovered territories—with terrible consequences for their inhabitants. This new knowledge was recorded and published in the form of reports, stories, in increasingly precise geographical maps, and in new scientific treatises. The result was a constant expansion and transformation of the worldview. In Leonardo’s library, too, the share of this new knowledge continued to grow over the years.

World in Motion <

- 101.

Mappa Mundi

ca. 1450

- 102.

Universalis cosmographia secundum Ptholemaei traditionem

et Americi Vespucii alioru[m]que lustrationes1507

- 103.

Das vierdte Buch von der Neuwen Welt. Oder neuwe und gründtliche Historien,

von dem Nidergängischen Indien, so von Christophoro Columbo im Jar 1492. erstlich erfunden1613

- 104.

Astrolabium (Amerigo Vespucci discovers the Southern Cross)

ca. 1590

- 105.

ca. 1491–1494

- 106.

ca. 1600

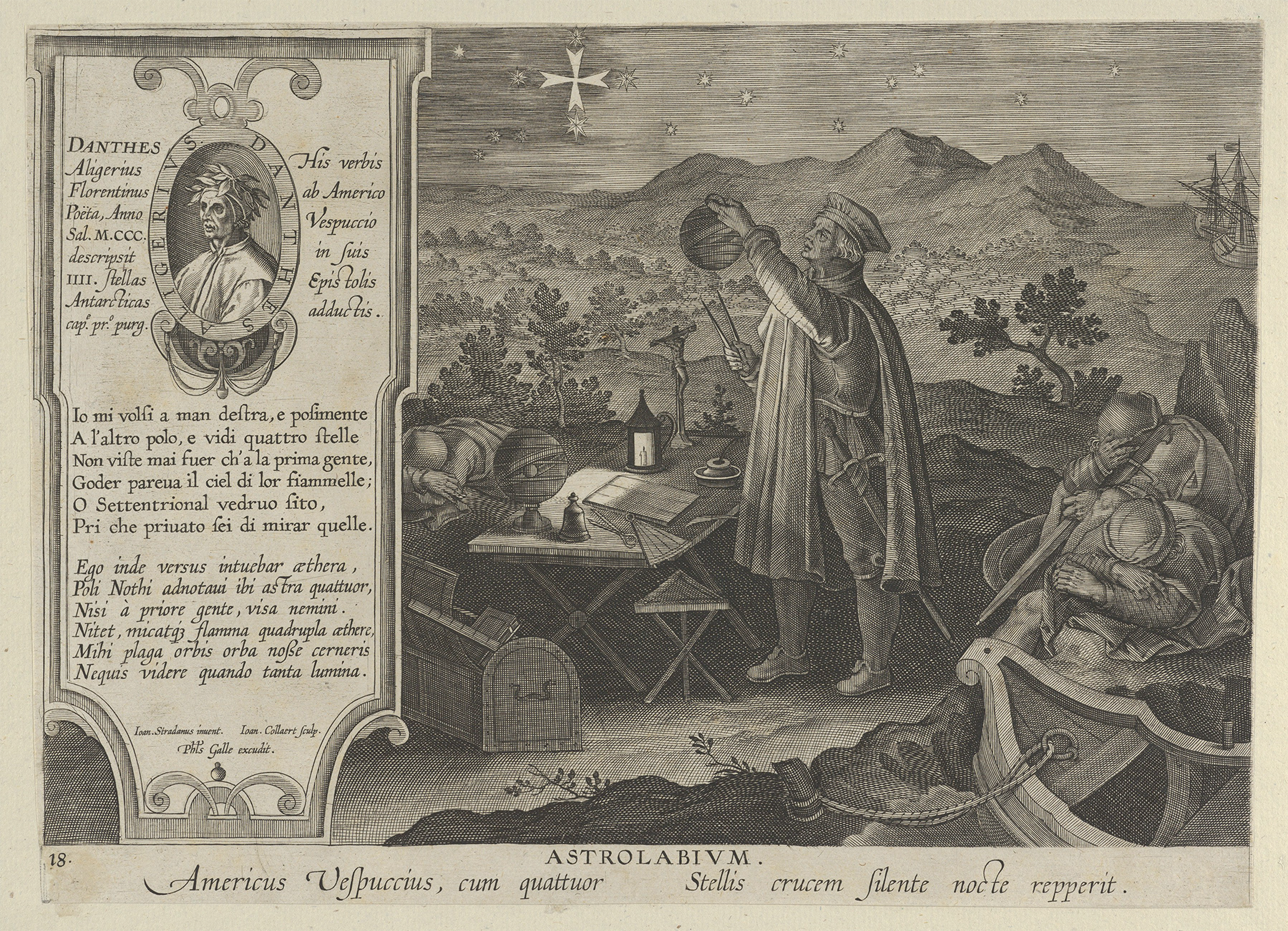

| 104.

Astrolabium (Amerigo Vespucci discovers the Southern Cross) ca. 1590 |

The Flemish engraver Jan van der Straet (1523–1605), who worked in Florence, presented important inventions and discoveries that were unknown to antiquity in his series of engravings, Nova Reperta. They included letterpress printing, spectacles, oil painting—and above all the New World. The discoverer after whom it was named, Amerigo Vespucci, a contemporary of Leonardo’s from Florence, is shown here locating the Southern Cross for the first time with the aid of an astrolabe (98 ●). The reference to Dante Alighieri doubly underlines the great contribution of people from Florence to discovering the New World—after all, the poet had prophesied the existence of the constellation in the southern hemisphere in the Purgatory section (I, 22ff.) of his Divine Comedy (21 ■). The atmospheric nocturnal scene is given an extra sacral touch by iconographical reminders of the biblical scene of the Agony in the Garden (Gethsemane) with the wakeful Christ and his sleeping disciples who let him down.

References

Baroni Vannucci, Alessandra, and Manfred Sellink, eds. 2012. Stradanus, 1523–1605. Court Artist of the Medici. Exhibition catalogue Groeningemuseum, Brügge, 9.10.2008–4.1.2009. Turnhout: Brepols.

Markey, Lia. 2012. “Stradano’s Allegorical Invention of the Americas in Late Sixteenth-Century Florence.” Renaissance Quarterly 65 (2): 385–442.

McGinty, Alice Bonner. 1974. “Stradanus (Jan van der Straet). His Role in the Visual Communication of Renaissance Discoveries, Technologies, and Values.” Ph. D., Medford, MA: Tufts University.

Palm, Erwin Walter. 1985. “Amerika oder die eingeholte Zeit. Zum Lob des Vespucci von Joannes Stradanus.” In Gedenkschrift für Gerdt Kutscher 2, edited by Anneliese Mönnich, Berthold Riese, and Günter Vollmer. Indiana 10. Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 11–17.