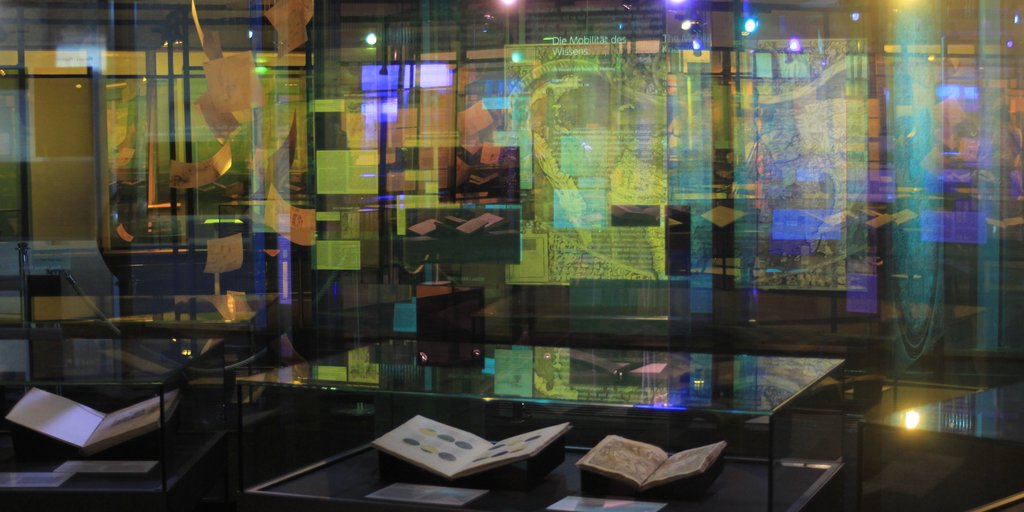

The Mobility of Knowledge <

Wisdom is the daughter of experience

Leonardo da Vinci

Codex Forster III, fol. 14r

The knowledge gathered by Leonardo in his personal library is collective knowledge. It is based, first, on a long tradition dating back to antiquity, and second, on increasing human mobility since the late Middle Ages. Oceanic navigation and the growth of printing created another major push. Merchants traveled along the major trade routes and maintained branches in important urban centers; participants in the Crusades brought knowledge to Europe, especially from the Arab world; international scholars and students exchanged ideas at the universities thanks to the universal language of Latin; artists and master builders traveled across Europe and beyond in search of lucrative commissions and the latest artistic developments. Explorers on voyages of discovery undertook daring expeditions to hitherto unknown continents and brought back new knowledge, while the colonizers who followed them seized the newly discovered territories—with terrible consequences for their inhabitants. This new knowledge was recorded and published in the form of reports, stories, in increasingly precise geographical maps, and in new scientific treatises. The result was a constant expansion and transformation of the worldview. In Leonardo’s library, too, the share of this new knowledge continued to grow over the years.

World in Motion <

- 101.

Mappa Mundi

ca. 1450

- 102.

Universalis cosmographia secundum Ptholemaei traditionem

et Americi Vespucii alioru[m]que lustrationes1507

- 103.

Das vierdte Buch von der Neuwen Welt. Oder neuwe und gründtliche Historien,

von dem Nidergängischen Indien, so von Christophoro Columbo im Jar 1492. erstlich erfunden1613

- 104.

Astrolabium (Amerigo Vespucci discovers the Southern Cross)

ca. 1590

- 105.

ca. 1491–1494

- 106.

ca. 1600

| 105.

ca. 1491–1494 |

The original version of this globe, also known as the Erdapfel (lit. earth apple), is preserved in the German National Museum in Nuremberg. It is the oldest representation of the Earth in the form of a globe. Commissioned by the council of the trading metropolis of Nuremberg, it was designed by the merchant and sailor Martin Behaim (1459–1507). Numerous arithmeticians, artists, and craft workers were involved in its production. A wide variety of sources including ancient authorities such as Ptolemy (90 ■), Strabo (89 ■), and Pliny (52 ■), together with contemporary travelogues and Behaim’s own experience, contributed to the encyclopedic depiction with hundreds of pictograms, place names, and descriptions. Precise cartographical representations intermingle with fantastical island kingdoms and exotic mythical creatures. But one can look in vain for the American continent. By the time it was finished, this showpiece, made in the same period as Columbus’ voyage of discovery, was already outdated.

References

Bott, Gerhard, ed. 1992. Focus Behaim Globus. Exhibition catalogue Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, 2.12.1992–28.2.1993. 2 vols. Nuremberg: Germanisches Nationalmuseum.