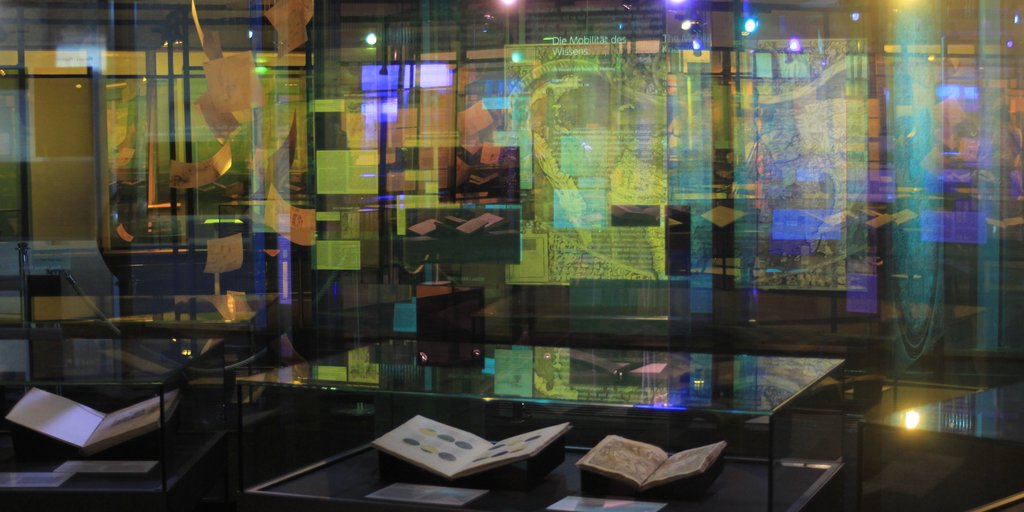

The Mobility of Knowledge <

Wisdom is the daughter of experience

Leonardo da Vinci

Codex Forster III, fol. 14r

The knowledge gathered by Leonardo in his personal library is collective knowledge. It is based, first, on a long tradition dating back to antiquity, and second, on increasing human mobility since the late Middle Ages. Oceanic navigation and the growth of printing created another major push. Merchants traveled along the major trade routes and maintained branches in important urban centers; participants in the Crusades brought knowledge to Europe, especially from the Arab world; international scholars and students exchanged ideas at the universities thanks to the universal language of Latin; artists and master builders traveled across Europe and beyond in search of lucrative commissions and the latest artistic developments. Explorers on voyages of discovery undertook daring expeditions to hitherto unknown continents and brought back new knowledge, while the colonizers who followed them seized the newly discovered territories—with terrible consequences for their inhabitants. This new knowledge was recorded and published in the form of reports, stories, in increasingly precise geographical maps, and in new scientific treatises. The result was a constant expansion and transformation of the worldview. In Leonardo’s library, too, the share of this new knowledge continued to grow over the years.

World in Motion <

- 101.

Mappa Mundi

ca. 1450

- 102.

Universalis cosmographia secundum Ptholemaei traditionem

et Americi Vespucii alioru[m]que lustrationes1507

- 103.

Das vierdte Buch von der Neuwen Welt. Oder neuwe und gründtliche Historien,

von dem Nidergängischen Indien, so von Christophoro Columbo im Jar 1492. erstlich erfunden1613

- 104.

Astrolabium (Amerigo Vespucci discovers the Southern Cross)

ca. 1590

- 105.

ca. 1491–1494

- 106.

ca. 1600

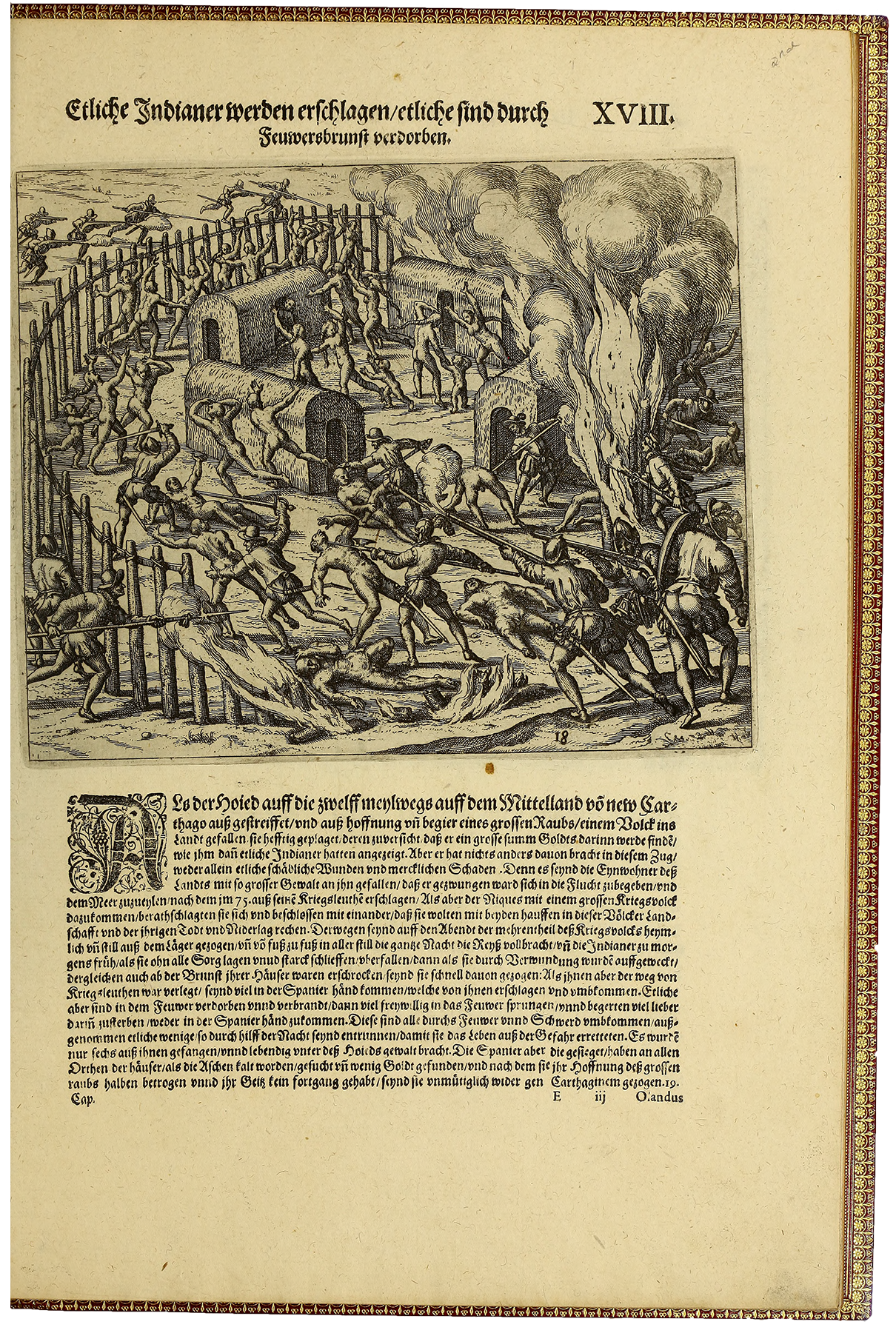

| 103.

Das vierdte Buch von der Neuwen Welt. Oder neuwe und gründtliche Historien, 1613 |

The Fourth Book of the New World was published by the Frankfurt publishing house of Theodor de Bry (1528–1598), an engraver originally from Liège, and his successors Johann Theodor de Bry (1561–1623) and Matthäus Merian (1593–1650). Between 1590 and 1634 they published a particularly comprehensive 14-volume anthology of travelogues from the newly discovered continents (which were still generally called the West and East Indies at that time). Aimed at an international readership, they were available in Latin as well as German. The famous fourth volume (first published in 1594) was a new illustrated edition of the Historia del Mondo Nuovo by Girolamo Benzoni (1565), based on eyewitness accounts. In his engravings, De Bry, who never visited America, superimposed ethnographical sources with typologies from the European visual tradition. De Bry, a Calvinist, used the opportunity to indict Catholic Spain as a world power, for example, by invoking the biblical scene of the Massacre of the Innocents in Bethlehem in this haunting picture of a massacre by Alonso de Ojeda’s troops.

References

De Bry, Theodor. 2019. America. Sämtliche Tafeln 1590–1602. Edited by Michiel van Groesen. Cologne: Taschen.

Greve, Anna. 2004. Die Konstruktion Amerikas. Bilderpolitik in den “Grands Voyages” aus der Werkstatt de Bry. Europäische Kulturstudien 14. Cologne: Böhlau.

Keazor, Henry. 1998. “Theodore De Bry’s Images for ‘America.’” Print Quarterly 2, June (15): 131–149.